A DANGEROUS GAME

At first glance the I.G.S.M. 1854 with clasp, Persia, is not a very exciting award, and certainly for most of the recipients the Campaign involved long cold marches culminating in the frustration of having the enemy flee further away at the first shot. However, set like diamonds in the mass of rather mundane detail are several very gallant actions and the medals to the men involved have a definite appeal.

At first glance the I.G.S.M. 1854 with clasp, Persia, is not a very exciting award, and certainly for most of the recipients the Campaign involved long cold marches culminating in the frustration of having the enemy flee further away at the first shot. However, set like diamonds in the mass of rather mundane detail are several very gallant actions and the medals to the men involved have a definite appeal.

PHASE 1

The 1856–1857 Campaign in Persia was a direct result of British fear that Russia intended to invade India through Afghanistan. After the Crimean War, Persia, sponsored by Russia, had occupied the town of Herat which was considered by strategists in Simla as “key to Afghanistan and thus Northern India.” In order to compel Persia to withdraw from Herat two plans were proposed. The first was to send a land force north through the wild regions of Afghanistan direct to Herat; the second to send an amphibious force south to attack Persia through her ports in the Persian Gulf. The latter plan was adopted.

In Persia itself relations between the British Representative Mr. Murray and the Shah were strained indeed. The Shah had been adopting a policy of increasing hostility towards British interests and complained that “Mr. Murray was stupid, ignorant and insane and has the audacity and impudence to insult even Kings” and that “unless the Queen of England herself makes us a suitable apology for the insolence of her envoy, we will never receive her foolish Minister, who is a simpleton.” The Shah also complained that Murray was carrying on an intrigue with the wife of the Persian First Secretary and “to stop the scandal” the Shah put the unfortunate lady into prison. This unromantic act was the culmination of many incidents and on November 1, 1856, the Governor–General of India, acting on behalf of the British Government, issued a proclamation declaring war on Persia.

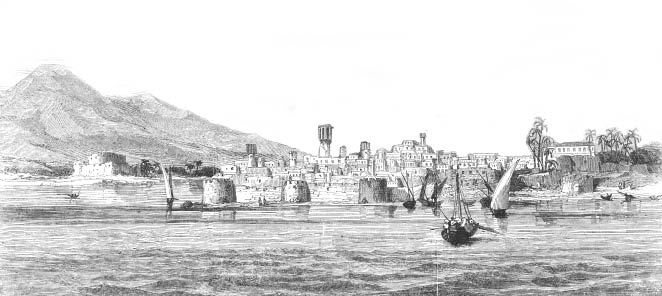

As the initiative for the declaration of war had come from Britain, it is understandable that the Services had begun to prepare for its eventuality long before November. The Quarter Master General, with a great deal of foresight and an equal amount of audacity, had sent Lieutenant J. Ballard, Superintendant of the Intelligence Department, to carry out an initial reconnaissance. This officer landed quite brazenly at Bushire and in front of the populace surveyed the fortifications using a compass and measuring chains until asked to leave by the Persian Authorities.

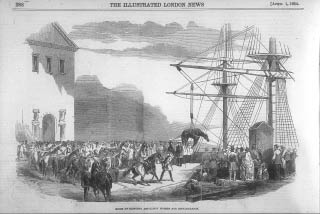

Final instructions for the expeditionary force reached Bombay on October 23, 1856, and within 4 days the first division had sailed. It was very much a Bombay Army affair:

H.M. 64th Foot, Lt-Colonel J. Draper

2nd Bombay European Light Infantry, Lt-Colonel J.S. Ramsey

2nd Balooch Battalion, Captain L.S. Hough

4th Bombay Native Infantry, Lt-Colonel R.W. Honner

20th Bombay Native Infantry, Lt-Colonel A. Shepheard

3rd Bombay Native Cavalry (2 Squadrons), Major J. Forbes

Poona Horse (1 Squadron), Lt-Colonel T. Tapp

3rd Light Field Battery

(1ST Company 1st Battalionn Bombay Artillery),

Captain S. Hatch

5th Light Field Battery

(4th Company 1st Battalion Bombay Artillery),

Captain H.L. Gibbard

3rd Troop Bombay Horse Artillery, Captain E.S. Blake

2nd Company Bombay Sappers & Miners, Captain C.T. Haig

4th Company Bombay Sappers & Miners, Captain J. Le Mesurier

The force commanded by Major General F. Stalker landed virtually unopposed at Reshire near Bushire on December 4, and by the 9th, General Stalker felt strong enough to take the initiative. The 64th Foot had twenty–seven Officers and 934 other ranks and the 2nd European Regiment had twenty–two officers and 907. Their first objective was an old Dutch fort at Reshire and the history of the 64th describes what happened:

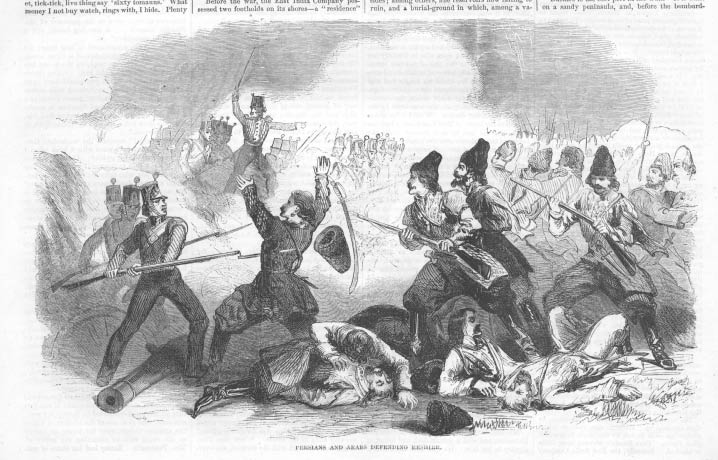

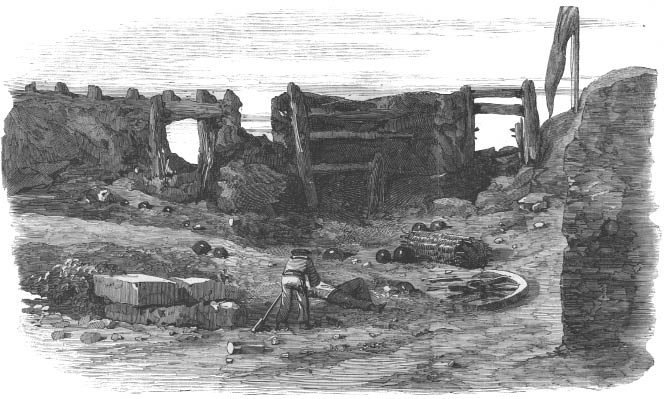

“On the morning of 9th December, General Stalker marched to attack the Persians, who had collected a considerable force, and by noon the enemy were observed in the village of Reshire, where, amid the ruins of old houses, garden walls and steep ravines, they occupied a formidable position. After some smart skirmishing, the Arab levies made a headlong retreat to their works around the Fort of Reshire, but wall after wall was surmounted and finally they were driven to their last defence, the old Dutch Fort of Reshire, bordering on the cliffs where they offered a strenuous resistance. The English Infantry leaped into the ditch and charged up an embankment of loose sand and stones, however, in ascending Brigadier J. Stopford was shot dead just as he reached the top. On the fall of the Brigadier, the 64th, the 20th Native Infantry, and 2nd Europeans, charged side by side with the bayonet, and speedily expelled the enemy, who fled in despair down the cliffs, where many met with their death trying to escape through the ravines; a number also were cut up by the cavalry, Colonel G.G. Malet of the 3rd Bombay Cavalry unfortunately falling in the pursuit.”

The 2nd European Regiment had two men killed and six wounded, though two of the three Officers who had been wounded, Lieutenants M.C. Utterson and W.B. Warren subsequently died of their wounds. Captain J.A. Wood, 20th Native Infantry who received six wounds when he led the Grenadier Company of his Regiment into the Fort became the first man of the India Army to get the newly instituted Victoria Cross. The Subadar–Major of the 20th was also recommended for a cross but at that time the decoration was not open to Indian soldiers and so the recommendation was rejected.

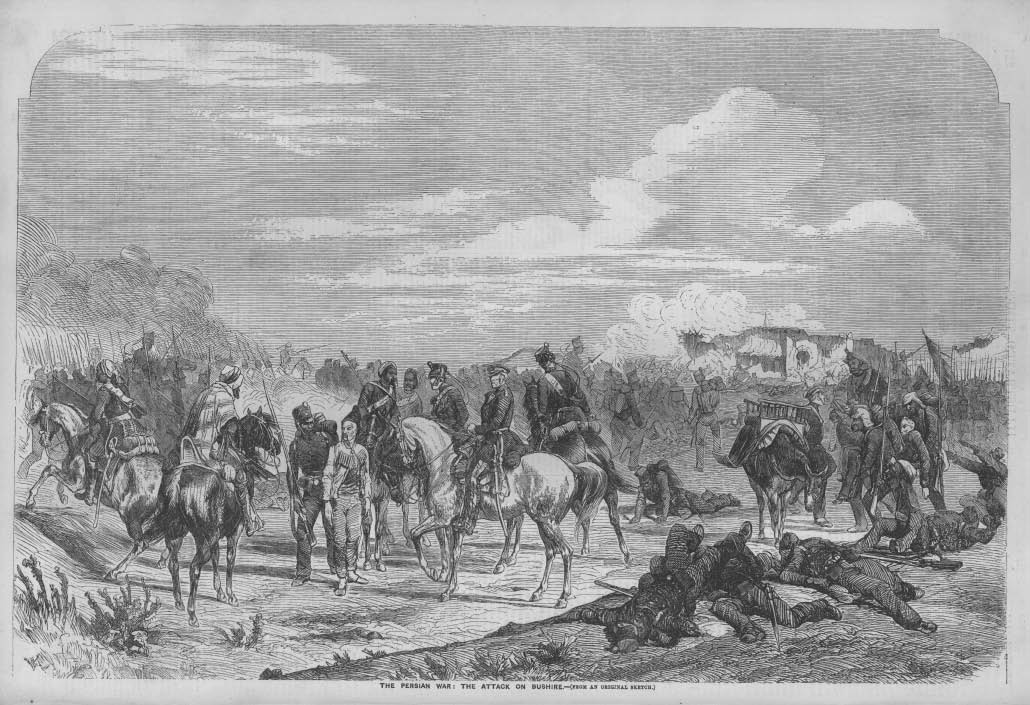

On the following day the fleet sailed to Bushire where the Persian troops were seen to be drawn up and preparing to defend. Rear Admiral Sir H. Leeke bombarded the town from the sea and the General Stalker’s forces formed up for the land assault. When they had advanced to within 500 yards, however, the flag–staff was seen to fall as a token of surrender and more than 1,500 men laid down their arms without firing a shot. (Many of these arms were muskets given to the Shah some years before by the British, in order to strengthen his defences against Russia). The British troops felt a keen sense of anti–climax at this surrender but now began to prepare for an offensive against the Shah’s main army.

In spite of this initial success gained by General Stalker, it was decided in India that a second division of troops should be sent to Persia to be commanded by General Sir H. Havelock, and that General Sir J. Outram should be sent to command both divisions.

General Outram was in England on sick leave at the time, but when he heard the news he made a “remarkable recovery” and sailed immediately for India. Outram, like many Generals serving in India, had been passed over in promotion by a number of junior Officers who had just fought in the Crimean War. He was therefore delighted at this opportunity of a large field command. General Havelock was also thrilled with the news, he was sixty–two years of age and the Campaign offered him a fresh chance for promotion.

Havelock’s Second Division was as follows:

4th Troop Bombay Horse Artillery, Captain G.P. Sealy

1st Company 2nd Battalion Bombay Foot Artillery, Captain J.H. Worgan

4th Company 4th Battalion Bombay (Native) Artillery, Captain J.G. Lightfoot

14th King’s Light Dragoons, Lt-Colonel C. Steuart

1,000 Scinde Horse (Jacob’s Horse), Colonel J.J. Jacob

78th Highlanders, Lt-Colonel H.W. Stisted

23rd Bombay Native Light Infantry, Major R. Travers

26th Bombay Native Light Infantry, Lt-Colonel G. Macan

As General Outram felt that cavalry was going to play a large part in the campaign. He requested that Colonel John Jacob, C.B., Commander of the Scinde Irregular Horse, be appointed to command all the cavalry units. After a degree of difficulty, for Jacob’s bitter tongue and forceful manner had made him many enemies, this was agreed and Jacob was promoted to local Brigadier. Major Henry Green took command of the Scinde Horse.

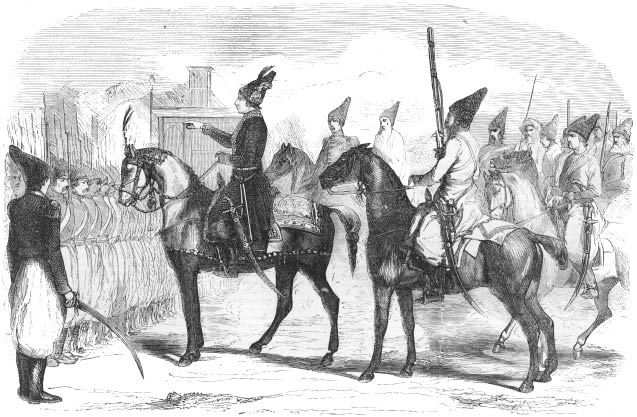

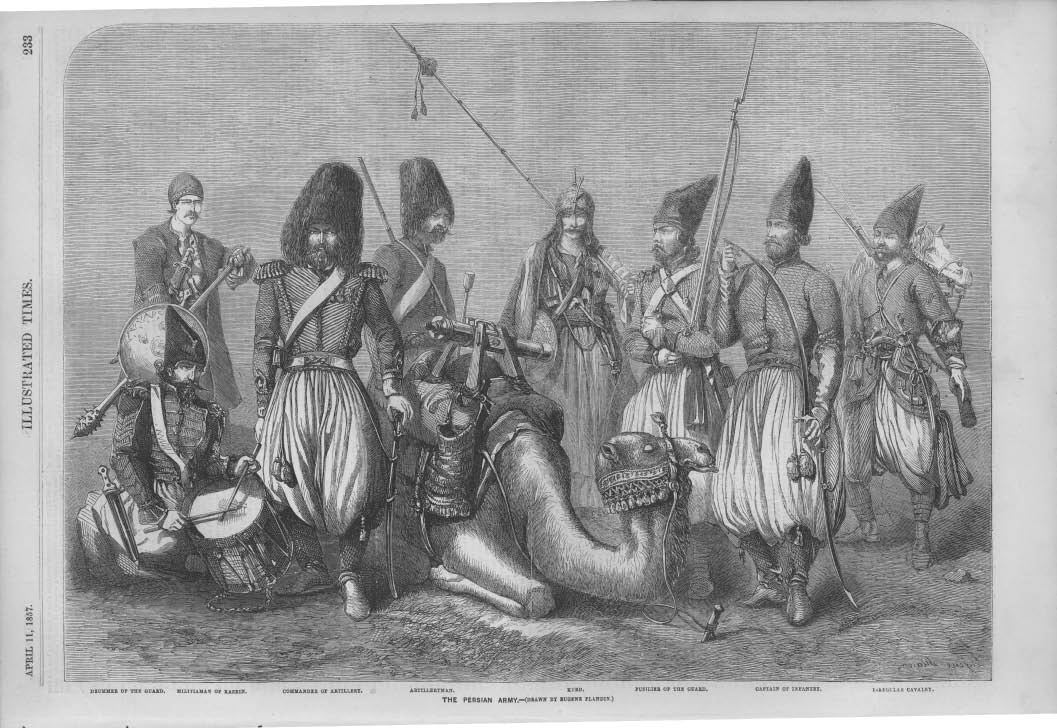

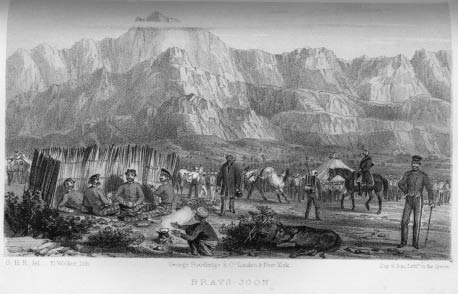

By February 3, the major part of the Second Division had arrived at Bushire. General Outram decided to confront an enemy force which was reported to be planning an attack on Bushire. The Commander-in-Chief of the Persian army Sooja-ool-Moolk had formed an entrenched camp at Borasjoon, about forty-six milesinland from Bushire, under the mountains. Here he had about 7,000 troops and eighteen guns, with promised reinforcements of twelve regiments, and thirty-five guns.

The march proved to be a cold wet trudge through mud and rain and, as the troops had left their blankets and tents behind in order to make better speed, everyone was extremely tired and miserable by the time the Persian position was finally reached. On their arrival, however, it was only to discover that the Persians had retreated once more and the troops were merely employed on destroying large stocks of enemy food and war material. At 8 p.m. on the 7th General Outram ordered the withdrawal to Bushire and after a short march the troops stopped to see a “great and unforgettable explosion” of 36,000 pounds of captured shot and shell.

The firing of this pile of ammunition was carried out by Lieutenant T.B. Gibbard and Lieutenant R.D. Hassard, 2nd European Light Infantry, who stood 150 yards away and fired “shell bullets recently invented by Colonel J. Jacobs”. The troops then resumed their night march.

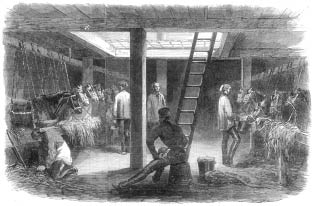

After several hours of marching, excited shouts, shots and bugle cries were heard from the Rear Guard commanded by Colonel R.W. Honnor and the troops halted and took up defensive positions. Although it was pitch black, the never–ending practice drill parades done by the soldiers now paid dividends.

For, with very little fuss the troops formed a large square interspersed with field guns, while skirmishers moved out in front to cover the gaps. The camp followers and equipment collected in the centre.

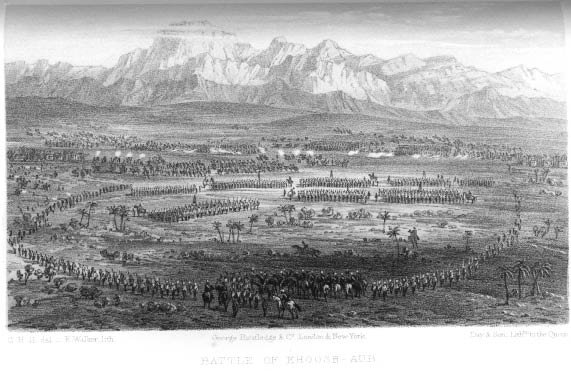

For about an hour Persian horsemen circled the troops, dashing up to shout obscenities, shoot and then retreat back into the dark. The British troops, like Brer Rabbit in the briar patch, “lay still and did nothing.” When dawn eventually broke it revealed the enemy, some 6,000–7,000 strong, formed up in battle order on a small hill near the village of Kooshab. Outram deployed for an immediate attack and arranged his infantry into two lines. He gave the order “Advance” and in “beautiful steady order”, the infantry fixed bayonets and moved forward, the 78th commanded by Major C.C. McIntyre and the 26th Native Infantry in the front rank, with the 64th and 20th Native Infantry in the second.

It proved to be another frustrating day for the infantry. They were shelled during the advance but the enemy continually moved back beyond the reach of their rifle fire and consequently it turned out to be solely an artillery and cavalry action. The British losses from the shelling were fairly light and were mainly in the second line as the Persians fired high. In the 2nd Europeans, three men were killed and Lieutenant E.M. Woodcock and eight were wounded. In the 64th, three men were killed with Captain R. Mockler, Lieutenant D.D. Greentree and fourteen men wounded. Lieutenant D.D. Greentree subsequently had his leg amputated. Colonel R.W. Honnor had a bullet in his saddle but the 78th had no casualties and in the 26th only one man was killed.

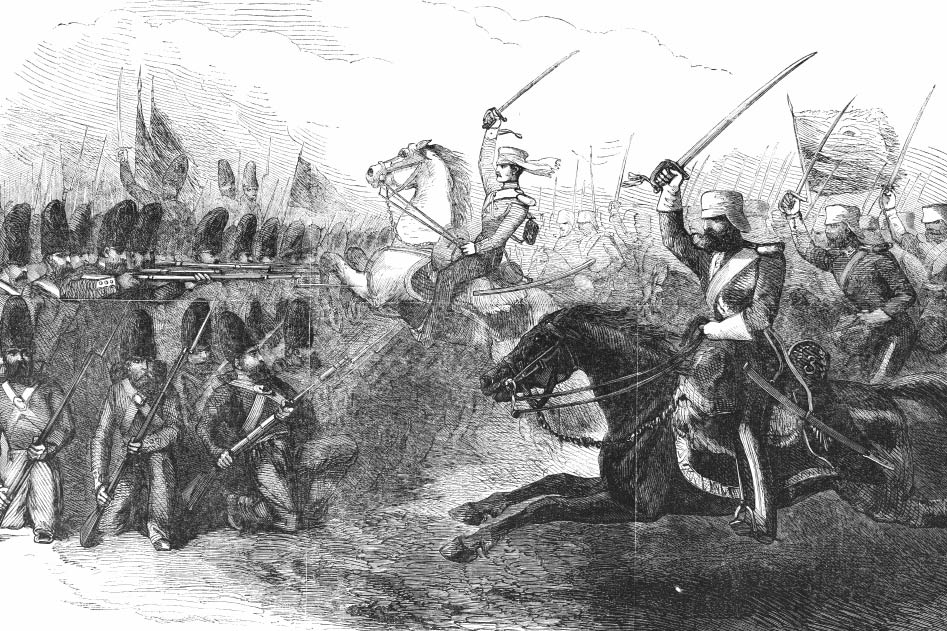

The bright event of the day was undoubtedly the charges made by the Poona Horse and 3rd Native Cavalry. The Poona Horse under Lt-Colonel T. Tapp captured a standard, but the 3rd Native Cavalry under Major J. Forbes and Lieutenant A.T. Spens were faced by that most forbidding of all prospects, a 500 strong battalion, formed up in square. Major Forbes, however, did not hesitate and led his 240 sabres forward to crash through their lines, though he himself fell severely wounded. General J.J. Jacob thought it was “the best cavalry performance of modern times” though he was most intrigued that “the destruction had been inflicted by the straight sword drawn from a steel scabbard – the very weapon said to be useless in the hands of a Native dragoon.”

Sixteen British soldiers were killed including Lieutenant A.C. Frankland and over 700 Persian dead were counted.

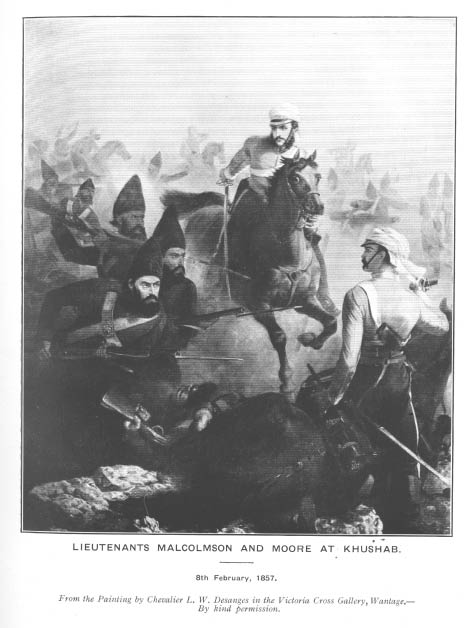

General Outram, who was notoriously generous with his awards, recommended ten of the 3rd Regiment for the Victoria Cross, but it was given only to Lieutenant A.T. Moore and Lieutenant J.G. Malcolmson. The story of how these two young subalterns won their Victoria Crosses is a schoolboy’s dream. Arthur Moore reached the Persian square a good length in front of his companions but as he leapt into the middle of the enemy his horse was shot beneath him and he fell heavily to the ground. In the fall his sword broke in half and he staggered up defending himself as best he could. His friend John Malcolmson seeing his peril forced his way through the enemy, gave him a stirrup and then brought him out through the fighting to safety.

Phase 2

The next major step in the campaign was an amphibious assault at Muhammerah, thirty hours sailing further up the Persian Gulf. For this attack General Outram divided his force as follows:

No. 3 Light Field Battery, 6 guns (176)

No. 3 Troop, Horse Artillery, 6 guns (166)

14th Dragoons (troop, 166)

Scinde Horse (89)

64th Regiment (704)

78th Highlanders (830)

Light Battalion (920)

26th Bombay Native Infantry (716)

23rd Bombay Native Infantry (749)

Madras Sappers & Miners (124)

Bombay Sappers & Miners (109)

Under the command of General Jacob at Bushire there remained a Garrison consisting of two field batteries and the mountain train, the cavalry of the 1st Division, the 2nd European Light Infantry and three companies each from the 64th Foot under Captain G.W.P. Bingham, the 4th Native Infantry, 20th Native Infantry and the Baluch Battalion. Colonel N. Wilson, Colonel R.W. Honnor and Colonel T. Tapp also remained at Bushire.

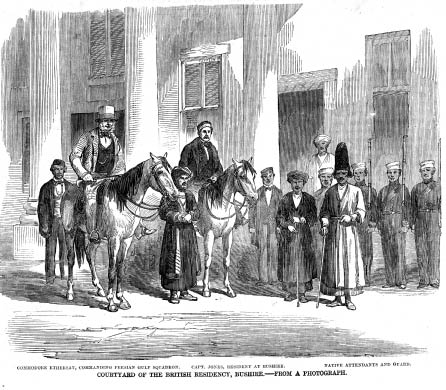

General Outram had initially intended that General Stalker should command at Bushire but, on March 14, just before Outram was sailing to join Havelock, General Stalker committed suicide. Equally strange was that three days later Commodore E. Ethersey, who had been appointed by Rear Admiral Leeke to remain in command of the Navy at Bushire with Stalker, also committed suicide. General Jacob, who was a very straight talking man, wrote pungently about the incidents in his journal:

“15th March: General Stalker shot himself during the night in dread of the responsibility of being left to command at Bushire during the absence of Sir James Outram.

16th March: General Stalker buried with full Military honours – a most injudicious proceeding in my opinion.”

The Commanding Officer of the 2nd European Light Infantry, Lt-Colonel J.S. Ramsey, was let go at this time. After the Regiment had left Karachi, the Ordinance Department accused him of “negligence in failing to apply for ball ammunition and disembarking 25,800 rounds short,” he was also accused of not making proper arrangements for the families left behind at Hyderabad. As a result Ramsey was removed from Command on the grounds that it was “beyond his abilities.” His successor was Lt-Colonel R. Shortreed who was fifty–five years of age but had spent his whole service with the Trigonometrical Survey Department and, according to the Regimental History “was plainly unfitted for command.” The Commander–in–Chief thought so too and soon appointed Lt-Colonel H. Stiles, 7th Native Infantry, to replace him. But Stiles did not arrive until March 6, and in the interval Shortreed did the best he could aided by Major E.A. Guerin, the Second–in–Command. When Outram selected his force for the Muhammerah attack he did not take the 2nd European Light Infantry and this, the Regimental History acidly complains, “is perhaps to be ascribed to the shortcomings of Shortreed as a Commanding Officer.”

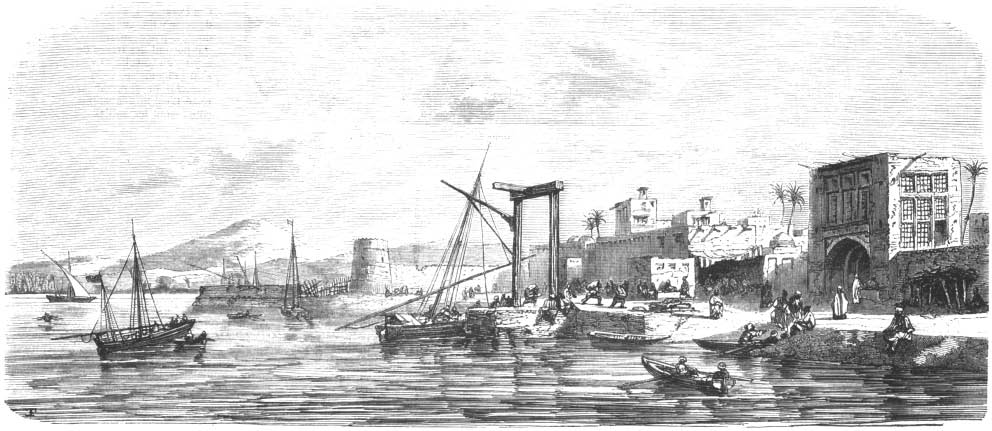

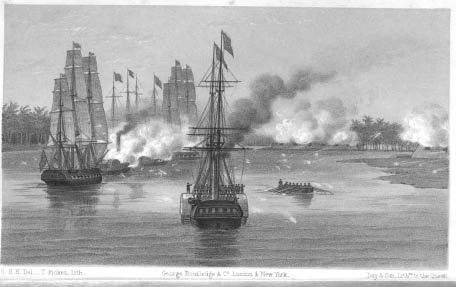

After several delays caused by orders and counter orders (all of which infuriated Brigadier Jacob), Outram felt himself ready to attack the Persian Army at Muhammerah. In the town were some 13,000 soldiers with thirty guns and as the British force was only 4,887 strong with twelve guns, an artillery bombardment was planned before the infantry assault. The critical factor was the location of the artillery and so, on the night of March 24, a party of sappers under Major A.M. Boileau set out in a small rowing boat to find a site. They discovered that the only suitable ground was too soft to bear the weight of the pieces and with a commendable degree of initiative constructed a raft. On the raft Captain John Worgan, Bombay Artillery, put two eight inch and two five and a half inch mortars and on the following night he was towed by the steamship Comet to a sheltered spot behind an island where he moored.

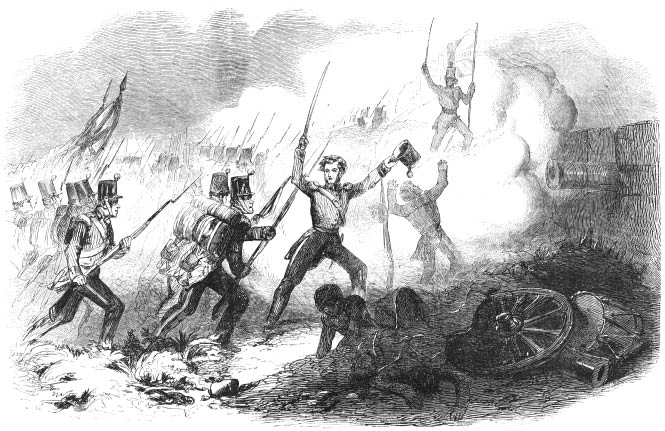

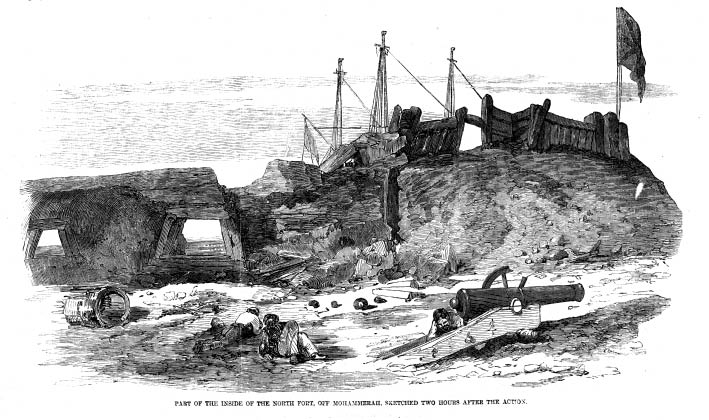

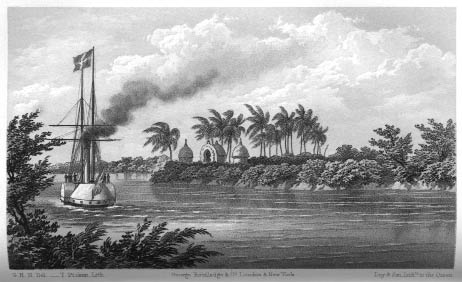

At daybreak on March 26, Worgan’s mortars began lobbing shells into Muhammerah. At the same time the Navy sailed up and began pounding from the front. Once more, however, the infantry bayonets were to be deprived of blood for under this unexpected artillery attack the Persian Army withdrew “at the double” leaving tents, guns and equipment all in wild confusion. Worgan was recommended for the Victoria Cross but this was not approved.

General Outram now deeply regretted that he had brought so little cavalry with him to follow up this retreat but he appointed his A.D.C. Captain Malcolm Green to command the 45 horses of the Scinde Horse he had and they performed magnificently. Captain Green formed them up in line abreast to give the impression they were the front line of a Cavalry Division and charged. The Persians accelerated their retreat and, although some 200 were killed, their army escaped.

The last phase of the Campaign was another remarkable and audacious deception. General Outram was told by his Intelligence Department that the enemy had retreated to Ahwaz approximately 100 miles up the Karoom River. He therefore sent 300 soldiers upstream in three small steamers to make a reconnaissance. They set off on March 29, consisting of 150 men of the Grenadier and Light Companies of the 64th Foot, with Captain W. Goode, Lieutenant G.H.J. Haldane, Ensign J.T. Pack and Assistant Surgeon E.L. Lundy, plus two companies of the 78th Highlanders under Captain J.D. MacAndrew, Lieutenant A. Cassidy, Lieutenant J. Finlay and Lieutenant G.D. Barker. All these troops were under command of Captain G.H. Hunt, who also had with him Major A. Kemball as Political Agent, Captain H. Wray, the D.A.Q.M.G., Captain M. Green the Military Secretary and Lord Schomberg Kerr as an observer. The history of the 78th describes what took place:

“Early in the morning of 1st April the three steamers proceeded towards Ahwaz and on nearing it the whole Persian Army was described posted in a stronghold on the right bank of the river, opposite the town. The small fleet steamed slowly up to within 3,000 yards of the position, when four large masses of the enemy’s infantry were made out lining the crest of a low range of sand hills which ran along their front; their left resting on the river bank. Three guns were posted near a small mosque in the centre of the position, a fourth being on a slope below, while on the right of the whole line was a horde of cavalry numbering over 2,000.

It having been ascertained from some Arabs that the garrison of Ahwaz did not exceed 500 infantry and thirty horses, it was determined to land a party, and if possible destroy the depot of stores and ammunition. Should, however, the place prove to be occupied in greater force, a simple reconnaissance was to be effected, followed by an orderly retirement to the boats under the fire of one of the gun–boats, which had been ordered to ascend the river for that purpose.

At 11 a.m. the troops commenced landing and at once advanced in three columns, covered by skirmishers; the whole party being extended in such a way as to present the appearance of regiments in brigade, and as the landing had taken place and these arrangements were made in jungle sufficiently high to conceal men, it was impossible for the enemy to form any correct estimate of the numbers. The left column consisted of the light company of the 78th, divided into skirmishers and supports, both in single rank, the remainder of the company marching in columns of threes, also in single rank. The grenadiers of the 64th and the remaining company of the 78th formed the right and centre columns in a similar formation. Two gun–boats were sent in advance up the river, and opened fire upon the enemy’s guns as soon as they came within range.

At twelve o’clock the troops approached the town, when the Arab sheik came out, and tendering submission stated that the town was undefended, the garrison having abandoned the place on the first appearance of the British advance. Within an hour and a half after the landing had been completed Ahwaz was in the possession of the British, without the loss of a single man; and the Persian Army consisting of 7,000 infantry, five guns, and a cloud of Bakhtiyaree horse, numbering over 2,000, was in full retreat leaving behind one gun, 154 stands of arms, fifty–six mules, a large flock of sheep, and an enormous quantity of grain, flour, wheat and barley.”

General Outram was greatly pleased by the expedition and wrote:

“A more daring feat is not on record than that of a party of 300 infantry, backed by three small river boats, following up an army of some 8,000 men, braving it by opening fire, deliberately landing and destroying the enemy’s magazines, capturing one of his guns in face of his entire army, and then actually compelling that army to fly before them.”

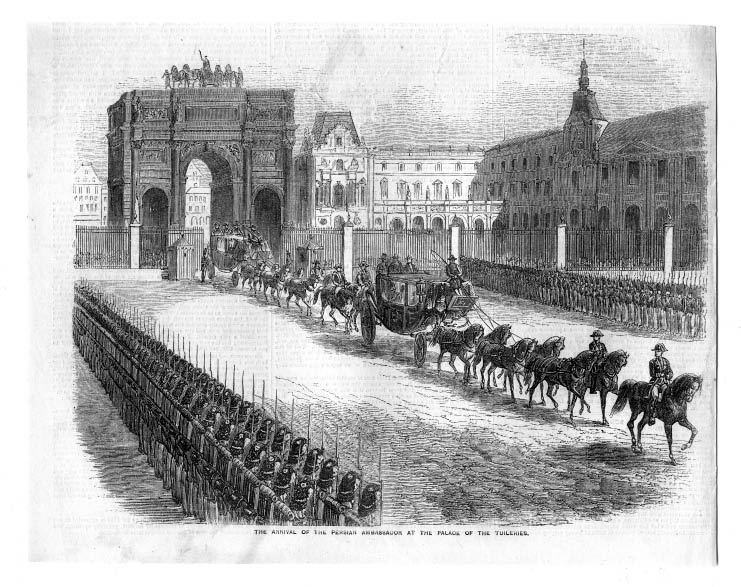

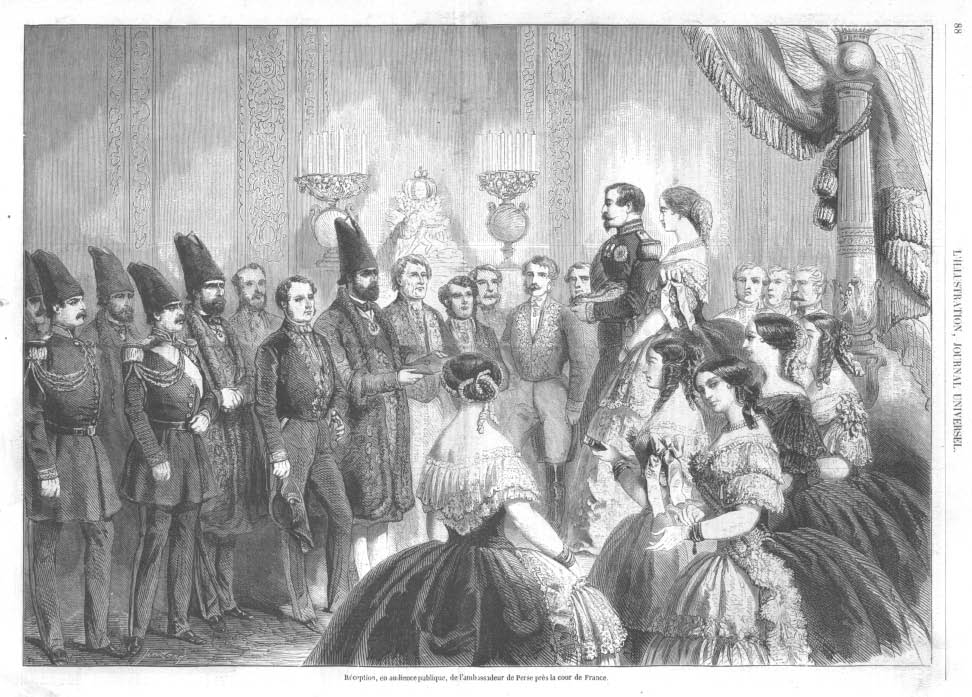

On April 5, the day that Captain Hunt’s force returned to Muhammerah, a peace settlement was agreed by the politicians in Paris and the Campaign was over. The troops remained in Persia for a few more weeks to ensure that the Shah would honour the Treaty and then sailed back to India.

It was fortunate indeed that the Campaign had proved so short and so few lives had been lost, for already the startling news had reached Outram that “there was serious discontentment in the Bengal Army.” The troops who had just earned the I.G.S.M. 1854 were soon to be thrown into the bloody battles of the Mutiny, and although their was criticism that Havelock had not been aggressive enough after Ahwaz, he showed no lack of initiative when he led the two same infantry regiments, the 64th and 78th, in the first Relief of Lucknow.